Brâncusi in AR

Brâncusi in AR

Tools of the Trade

The current Brâncusi exhibit returning to the MoMA from July 22nd to February 18, 2019 poses a moment of excitement, followed by several questions in my mind.

I can only only wonder what the poster child of modern sculpture would do with the tools we have available today – particularly as it pertains to the display of his work outside the intimate context of his studio!

Having participated in interactive museum exhibits both as guests and designers, we asked ourselves what it means to captivate and excite broader audiences, while also discussing different ways of engaging with art and design in an era of phone addiction.

Most importantly, our line of inquiry leads to 'contextualization' — how does an exhibit engender a deeper level of understanding in the artwork while conveying the importance of context, in this case of Brâncusi's Atelier. — and how, if at all, can it be edifying and entertaining?

In our effort to expand the life of artworks through deeper engagement and understanding, getting the audience to interact with works through modern mediums is becoming more broadly expected. It can be thought of as participatory, immersive or even interactive. People flock to exhibits offering the ability to engage in ways one wouldn’t have otherwise.

And one thing is clear: the current cultural expectation is hinged not only on entertainment and social sharing, but a novel engagement – few museums have yet to do right.

The Artist

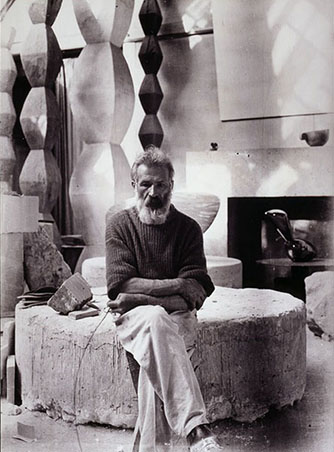

Born in Romania in 1876, Constantin Brâncuși [brɨŋˈkuʃʲ] lived and worked in Paris from 1904 until his death in 1957, where he embraced an experimental modern spirit, including an interest in modern tools, which attributed to his most productive time as a sculptor.

Rather than modeling clay like his peers, Brâncusi carved his work directly from wood or stone, or cast it in bronze. Simultaneously, he rejected realism, preferring that his sculptures evoke rather than resemble the subjects named in their titles. Brâncusi made bases for many of his sculptures, themselves complex constructions that became part of the work. He often moved works from base to base, or placed them directly on the floor of his studio, so that they lived in the world alongside ordinary objects, and among people.

From 1916 until his death, Brâncusi worked in various studios, at first 8, then 11 Impasse Ronsin in Paris's 15th Arrondissement. He used two and then three studios, knocking down the walls to create the first two rooms in which he exhibited his work. In 1936 and 1941, he added two other adjoining areas, which he used for works in progress, and to house his workbench and tools. This which is where he produced the majority of his work.

The Artist (and his Studio)

Brâncusi considered the relationship between sculptures and the space they occupied to be of crucial importance. In the 1910s, by laying sculptures out in a close spatial relationship, he created new works within the studio which he called "mobile groups", stressing the importance of the connections between the works themselves and the possibilities of each for moving around within the group.

In the Twenties the studio became an exhibition space for his work, and a work of art in its own right: a body consisting of cells that all generated each other. This experience of looking from within the studio at each of the sculptures, thus perceiving a group of spatial relationships, led Brâncusi to revise their positions every day to achieve the unity he felt most apposite.

At the end of his life, Brâncusi stopped creating sculptures and focused solely on their relationship within the studio. This proximity became so fundamental that the artist no longer wanted to exhibit, and when he sold a work, he replaced it with plaster copy so as not to destroy the unity of the group.

In his will, he entrusted his entire studio to the French state. After two attempts, an exact reconstruction of his Atelier was made by Renzo Piano in 1997 on the piazza opposite the Centre Pompidou to house his collection.

The Supercomputer in our Pocket

Hypothesizing Brâncusi's posthumous return to this very moment in time, perhaps we would be witnessing him sculpting not only wood, plaster and marble or casting bronze, but gracefully crafting impossible worlds out of bits and bites. VR headset on, his hands effortlessly gesturing through space, it would be an alluring performance to witness, possibly as much as seeing his hands at work through archival film.

From the audience's perspective such works would be viewed as AR sculptures, very likely enjoyed through the lens in our pocket, and a few years down the line – the actual lens caressing your face.

As adoring fans of Brâncusi and proponents of more engaging museum exhibits, we weighed the benefits and shortcomings of several technologies, from custom software to readily available apps – thinking not only about the level of engagement we wish we could personally have, but the tradeoffs of education and entertainment. As is always the case, there are several other layers and hierarchies of needs that require balance – from providing frictionless downloads, to intuitive usage, to the consideration of the widest audience.

And then there is of course the antithetical technology question –how to focus and reduce app use in favor of just being present and inspiring a sense of awe via the physical exhibit.

2 of 3 App Paths:

Snapchat + AR:

Bird In Space – contextualizes the notion of a sculpture in flight.

To cast a wide net, we set a preference for entertainment and ease of use through available platforms. Snapchat offers arguably seamless filter downloads, fluid interaction, paired with fantastic real world tracking. The limitation being a supremely small file size for us designers and developers. Boundaries being fuel for creative, we set out to artistically contextualize individual sculptures, expanding the canvas in to metaphorical space , in this case for the Bird In Space – a piece permanently on view at the MoMA, and as of this writing – on view globally, on any device running Snapchat!

Unity + AR

iOS AR prototype running on iPhone at the MoMA

AR prototype on iPad at the MoMA

Our second path focuses on deeper interaction, didactics and spatial immersion. For museum visitors this implies both an intrinsic desire to get the most out of an experience, as well as a willingness to engage with a curated tool. To achieve this we landed on a combination of tools and technologies – particularly: Photoshop, Cinema4D, Maya, AfterEffects, Unity3D and XCode.

After reconstructing several 3D models and spatial layouts from archival images, we export a baked lighting and texture setup and re-build the studio environment, followed by spatial triggers and user interactions in Unity. This stack allows for the App to be deployable to all major mobile platforms, where we are then leaning heavily on embedded tracking and positioning tech – Apples's ARKit and Android's CoreAR.

For the most fluid user experience, the intention is to allow visitors to roam around and explore, offering bits of information pertaining to specific pieces only when requested.

From the museum's perspective, acknowledging that visitors will wonder through a space glancing at a screen, requires a few new accommodation. Firstly, the spatial and architectural requirements are more akin to an open space, and secondly, the exhibit requires both physical boundaries and digital proximity alerts, which need to be baked in to the App. There are of course many ways to accommodate this new behavior, using tailored lighting cues, audio cues or combinations of haptic interference.

As is only a natural point of conversation in such endeavors, it needs to be said that the tradeoff of space is consequently that of restrained attendance and heightened supervision - a dynamic we do not advocate for. Let the people flow.

An Indulgence

Lastly, assuming we also had an annex for those inspired to create as well as much younger audiences for whom didactic approaches do not yet captivate attention – we weighed the benefits of a very laborious process of developing an interactive sculpting tool. This third idea, which we left on the table, was to give the audience the ability to create their own Brâncusi inspired objects, in 3D. Based on a visual language and materiality that is congruent with Brâncusi's, the result of most iterations would lead visitors to create their own Brâncusi inspired sculptures to be collaborated on, shared and possibly printed.

Immersive Context:

Atelier Brâncusi, Centre Pompidou, Paris – An exact reconstruction of his studio, housing his collection entrusted to the French state in 1957

The importance the Atelier played in Brâncusi's life can not be stressed enough – not only as a place to create and experiment with modern tools and materials, but as a work in itself, promoting a spatial and spiritual harmony between every sculpture, visitors and the room.

Pieces not in the exhibit are visible via our Unity based AR tool, contextualizing the intimate spacial dynamics Brâncusi spent the majority of his time arranging.

The idea of recreating the Atelier atmosphere in a digital and physical space (to the maximum extent a museum collection can allow) inevitably gives an audience the opportunity to experience the sculptures in the context the artist created and obsessed about, albeit a digital one.

In essence, Brâncusi's largest sculptural work – his actual body of work – can be experienced by any individual with a phone in their hand and a willingness to be immersed in an awe-inspiring environment.